Scientists at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine announced today that they have developed a new coronavirus vaccine candidate.

Early animal trials have shown good results so far, but human trials are still in the planning stages.

“We had previous experience on SARS-CoV in 2003 and MERS-CoV in 2014,” said Andrea Gambotto, co-senior author of the paper published in the journal EBioMedicine, and associate professor of surgery at the Pittsburgh School of Medicine..

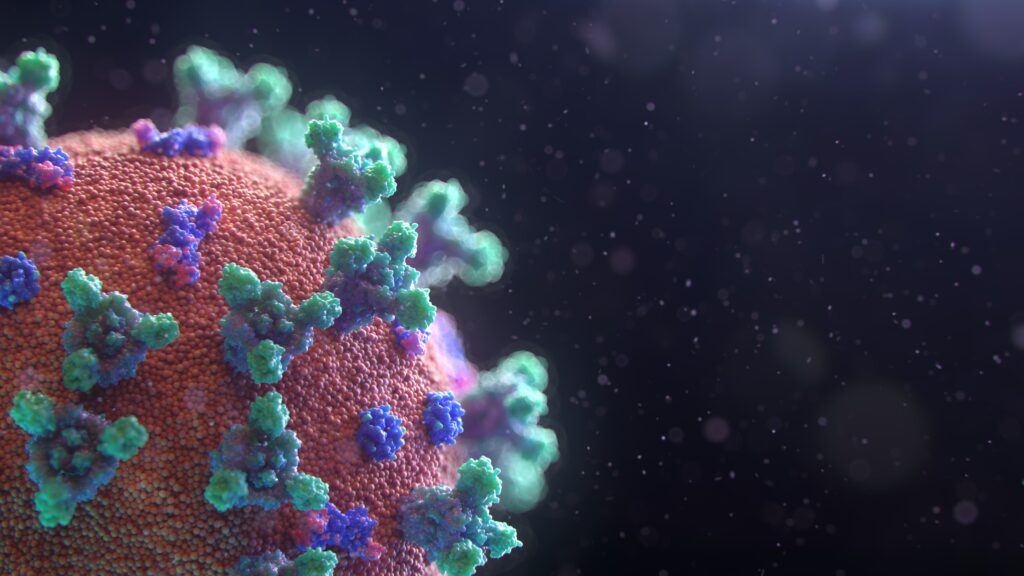

“These two viruses, which are closely related to SARS-CoV–2, teach us that a particular protein, called a spike protein, is important for inducing immunity against the virus,” Gambotto suggested. “We knew exactly where to fight this new virus.“

The vaccine named PittCoVacc (Pittsburgh Coronavirus Vaccine) works in the same basic way as a flu vaccine: By injecting lab-made viral protein into the body to build immunity.

When tested in mice, the researchers found that the number of antibodies capable of neutralizing the deadly SARS-CoV–2 virus were built up in the body two weeks after delivery.

The new drug is given through a microneedle array, a Band-Aid like patch made of 400 tiny microneedles. Once the patch is applied, the microneedles, which are made entirely of sugar and protein dissolve, leaving no trace behind.

“We developed this to build on the original scratch method used to deliver the smallpox vaccine to the skin, but as a high-tech version that is more efficient and reproducible patient to patient,” said co-senior author Louis Falo, professor and chair of dermatology at Pitt’s School of Medicine, in the statement. “And it’s actually pretty painless – it feels kind of like Velcro.”

Researchers said that these patches can be easily manufactured at an industrial scale. We need not refrigerate this vaccine during transportation or storage which is a big complication for other vaccines.

“For most vaccines, you don’t need to address scalability to begin with,” Gambotto said. “But when you try to develop a vaccine quickly against a pandemic that’s the first requirement.“

Scientists are currently applying for drug approval from the US Food and Drug Administration and will start human trials as soon as they get approvals.

“Testing in patients would typically require at least a year and probably longer,” Falo said.

Research was published in EBioMedicine